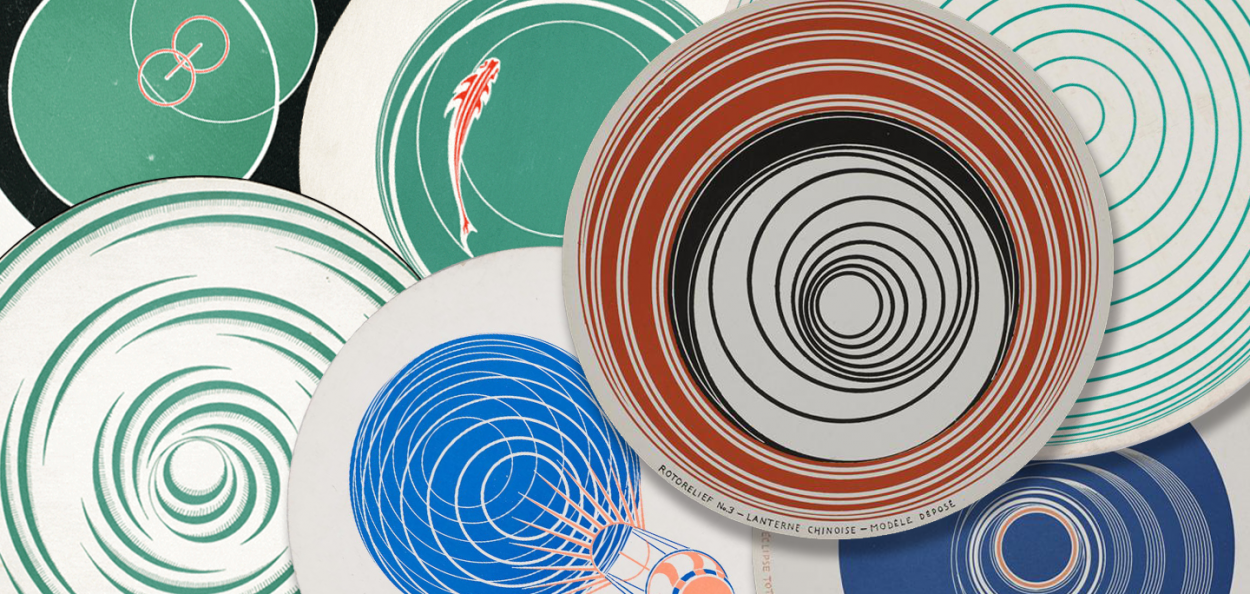

Marcel Duchamp’s interest in mechanical art and optical illusions led to the creation of his set of 6 discs known as Rotoreliefs. As an example of Duchamp’s ability to challenge the notion of what art is, Rotoreliefs can be seen as the next stage of his spinning, kinetic works—including his Precision Optics works and Anemic Cinema, a short movie clip that includes rotating images and spinning text, in collaboration with Man Ray in 1926.

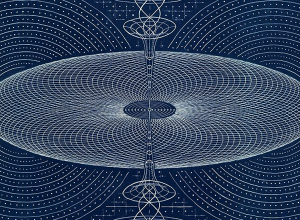

Duchamp initially displayed these optical experiments in 1935 at Concours Lépine inventor’s fair in France. Rotoreliefs or play toys, as Duchamp called them at first, contained no sound, hence, were considered as decorated discs. Their primary purpose was to be spun on a turntable at 40-60 rpm, not less not more, to create an optical illusion that would change one’s perception of depth. When Rotoreliefs were spinning, they seemed as if they were 3D.

Duchamp made 500 sets of Rotoreliefs. Some of them featured in experimental movies such as Jean Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet (1930) and in Hans Richter’s Dreams that Money Can Buy (1947). Sadly, 300 were lost throughout World War II, and to date, only a few of them can be found in Museums such as Guggenheim, Detroit Institute of Art, and Carnegie Museum of Art.

Eighty-three years after the initial display of his no-sound decoration discs, Duchamp’s Retoreliefs continue to remain exceptionally alluring.