Many enter the electronic music industry, yet few distinguish themselves from the rest. Among the few, only a handful can truly establish themselves under the definition of a pioneer. The Swiss composer and producer Thomas Fehlmann is a living example, without a doubt. Initially interested in pursuing a career in art at the Art Academy in Hamburg during the 1970’s, a life-changing meeting with experimental musician Conrad Schnitzler altered the course of his career forever. Fehlmann dropped the paintbrush and partnered with Holger Hiller to form the post-punk, electro-pop outfit, Palais Schaumburg. He and Hiller kickstarted the ‘80s with a fusion of disco, minimalism, jazz and funk into the early German electronic music scene.

Moving from Hamburg to Berlin in 1984 gave Fehlmann a revitalisation into the atmosphere of electronic music, as Berlin’s nightlife and electronic scene provided him with a chance to be heard. After Palais Schaumberg broke up in 1985, he founded the Teutonic Beats label three years later, known for collaborating with artists such as Jörg Burger, Wolfgang Voigt, Sun Electric and Westbam.

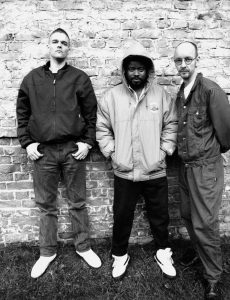

Fehlmann’s rise to fame allowed him to pair minds with revered musicians such as Moritz Von Oswald, later one half of Basic Channel and a producer who heavily influenced the rise of dub techno. As Fehlmann took his experimental avant-garde into the 1990’s, performing and producing under the moniker Ready Made. He formed yet another partnership, this time with Moritz Von Oswald and Juan Atkins as 3MB (acronym for 3 Men in Berlin), helping to cement the Berlin-Detroit connection.

During the ‘90s, he became a resident at the famous Tresor, an underground techno nightclub known for being a crucial feature of Germany’s electronic music scene and Berlin’s nightlife. In addition with Tresor, Fehlmann became involved with revered collective Ocean Club, which has been broadcasting a radio show since 1998.

Fehlmann’s work can easily be associated with iconic English electronic music group The Orb, in which he has been involved in many of their albums, eventually becoming a part-time member of the group. It was Fehlmann’s partnership with the frontman of the Orb, Alex Paterson, that truly crafted his intellect in the electronic music industry. The duo formed a lifetime friendship that fueled the success in each of their careers.

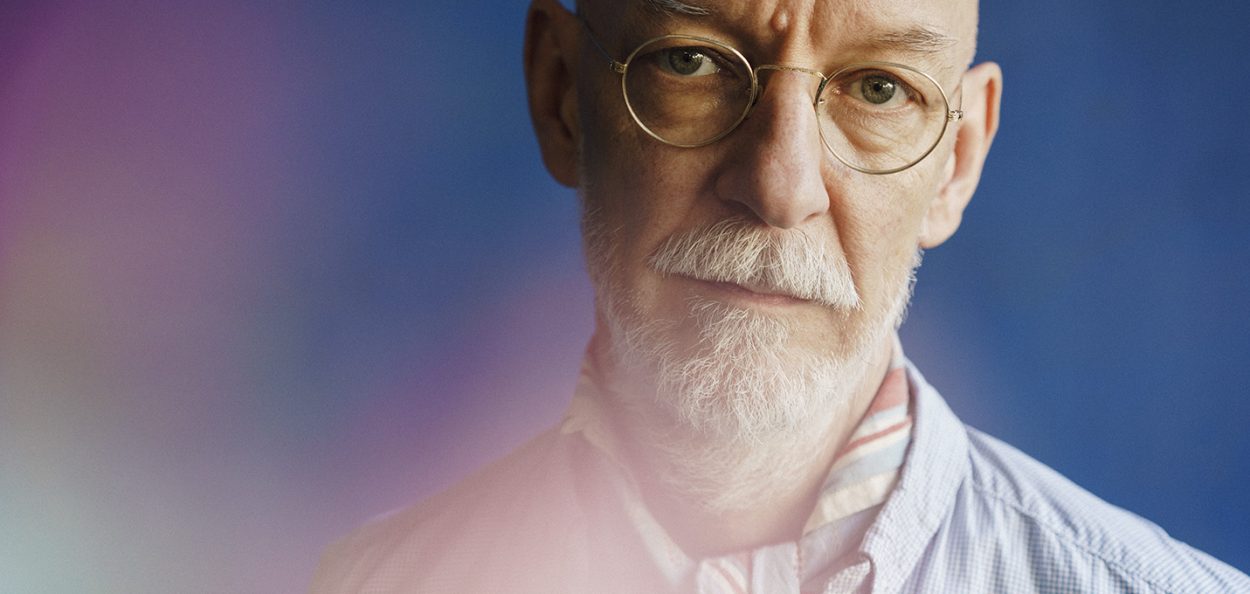

Between 1991 and 2018, Fehlmann has released seven solo albums, with the most recent one being under the Kompakt label, Los Lagos. The Zurich-born producer and composer is now 61 years of age, but it seems that he won’t be slowing down any time soon, finding himself in the world of techno “as a means to deconstruct and rebuild again; set up an area of tension, loose it in the flow of the grooves,” says Fehlmann. The pioneer will continue to search for his role in the dynamic aura of electronic music, instilling harmony and forever finding new ways to shape his music. We were graced with the opportunity to have Fehlmann with an exclusive interview and learn more about his long and productive career.

It is said that during the ‘70s, you had a life-changing meeting with experimental musician Conrad Schnitzler that would inspire you to peruse the world of music. What happened in that meeting and what pushed you in this direction?

Thomas Fehlmann: Yes, I came from Switzerland to study art in Hamburg, and I was lucky enough to have Conrad Schnitzler as a guest professor. His contribution was setting up a little studio in his workshop where students could enroll to experiment under his supervision. His specific yet light, humorous approach somehow became the cell of initiation. Everything was simple and direct. He was clearly on a mission, and I trusted his intuition. It was: work can become play and play can become work.

What or who were your early passions and influences?

TF: From ‘65 onwards I was strongly into The Beatles and started collecting 7” records. I couldn’t understand a word of English at the time and started making songs in some fantasy language to my ukulele. That might be a reason why I’m making instrumental music. The vocals were always a rhythmical part of the music, and the lyrics never had much of a meaning to me.

What is electronic music for you? What was that element that made you dedicate a whole life to it?

TF: Electronic music is an art form for me. I guess it was the unpredictability in the result and the do it yourself approach that attracted me most. As opposed to taking music-lessons, it was about creating the unheard. It made me think quite differently about what’s interesting to me in music and what’s more conventional. It’s not about fast fingers. It’s more mysterious, a search for surprises, you never know exactly where you will end up and how you will get there.

What is the main idea behind your project and what are the main characteristics of your sound?

TF: To tap into the unconscious, the urges to live out a non-verbal creativity. I get excited when it sounds broken and weird.

Do you remember when you first began to gravitate towards techno music?

TF: Oh yes, I listened to Kraftwerk from the first record onwards in the ‘70s and followed their transformation from semi-electronic hippy jams to tight, futuristically sequenced proto-pop. Then in ‘88 came the first Detroit compilation on 10 Records, then the wall came down, Tresor and Hardwax opened. That was that. In Berlin music suddenly was charged with social and political implications. It had MEANING. That had an incomparable impact. Bye, bye Ivory Tower!

How was the techno scene back in the day when you started working on it?

TF: It started small and cosy, family style. We all knew each other, and it was emotional. From there it grew to up to a million attendants at the Love Parade by the end of the ‘90s. Some things were lost on the way, and others gained. It was impressive to see how strong an impact this music scene had on the city and its society. There is this brilliant book I’d like to recommend on the Berlin perspective. It’s called Der Klang Der Familie: Berlin, Techno and the Fall of the Wall by Felix Denk and Sven von Thülen. It’s really epic. There’s even talk about a TV series.

What about Tresor and the whole Berlin-Detroit axis era?

TF: Tresor is still going strong, I will play there live very soon plus I enjoy the new Tresor offspring, the small OHM club and obviously the massive Kraftwerk. It gives Tresor a defined cultural role that is rare in its spectrum.

The Detroit-Berlin axis is alive and kicking too. Earlier this year, the Tresor label released a collaboration project I did with Terrence Dixon. It’s called We Take It From Here, and was recorded last year in Detroit.

Through your Teutonic Beats label, you became friends with Dr. Alex Paterson of The Orb. Can you tell us the story of how you met and eventually led to making music together?

TF: After our first meeting, he took me out to Shoom, which was a fabulous club at the time. He introduced me to some of his friends and shortly after I was hanging out at Jimmy Cauty’s house. That’s how one thing led to another.

Which are some of the albums that stand out for you in the vast catalogue of The Orb project?

TF: Orbus Terrarum, Moonbuilding 2703 AD, and COW / Chill Out, World!. Tomorrow I might say something different though.

Your first solo album came out in ’98 on R&S Records sublabel Apollo, titled Good Fridge. Flowing: Ninezeronineight. How would you describe the change in your sound since that time up until your latest album, Los Lagos?

TF: Find this difficult to answer. It’s looking back a little too much. I like to look forward, and I don’t want any weight from the past. For the most part, I can accept my work as temporary results in a constant search. My motivation is constant renewal. Still lots of work to do!

Can you tell us more about your last LP Los Lagos? What’s the story behind it and what are some of the most important tools and instruments you used in the album?

TF: I did set myself the challenge to make excessive use of my old Korg sequencer SQ-10, and I did, on all tracks. I recorded it and then cut it up, reduced and treated it. There’s a distance established when the sound of the sequence is recorded, but I need that step to be able to see clearly what I really want.

What are currently your main challenges and ambitions in terms of your approach to production?

TF: Well, the best record is still to be done. The current sport is focusing to switch off, so the head is following the hand and not the other way round. I was working on this for Los Lagos, and I felt much happier with the workflow. I think I’ve managed the less is more motto a bit better recently, but at the same time, it’s playing with your own rules. Take them to pieces and rebuild.

How has the process of making music transformed you in all these years?

TF: I believe it kept me sane and it gave me a firm belief in the beauty and the power of creativity.

Art can be a purpose in its own right, but it can also directly feed back into everyday life, take on a social and political role and lead to more engagement. Can you describe your approach to art and being an artist?

TF: Art had a major impact on my life. I got introduced to Picasso and Rauschenberg as a kid and looking back I think my fascination was simply “whaaat? really?” posing questions that not necessarily have an answer. Venturing out of the ordinary. The interplay between the bad that becomes good, and its reversal is a constant drive that is asking to be tested every day. Of course, all of this is inseparable from social and political implications and context.